The Jungle And The Sea is an ambitious epic and companion piece to Counting and Cracking, the award-winning hit of the 2021 Sydney Festival and 2022 Edinburgh Festival. S.Shakthidharan and Eamon Flack, co-writers and co-directors, are back with many of the same cast. The Jungle And The Sea is extraordinary, powerful yet nuanced. It compells us to question whether peace is possible after significant societal trauma without properly accounting for the past. Can justice be done without a telling of all truths?

The action follows a Hindu family during the Sri Lankan civil war. Between 1983 and 2009, terrorism and state violence pitted the majority Sinhala and minority Tamil populations against one another in the continuance of an ancient struggle, exacerbated by British colonialism and capitalised on by the government. The writers draw on two classical texts for structure; a Sanskrit epic Mahābhārata and an Athenian tragedy Antigone, both set during civil wars.

Act I begins with Gowrie, seated alone and blindfolded. She begins an ancient, graceful dance, and presents a conch shell. The peace is abruptly broken with the news "they found the bodies". We are back in time to meet Gowrie's family in happier, carefree times. A game of cricket interrupted by bombing. An ominous foretelling "the ball is in the air; it must be caught". Only son Ahilan joins the Tamil Tigers. The father Siva, now blind, flees to the safety of Sydney with atheist daughter Lakshmi. Gowrie and daughters Abi and Madhu stay behind on a quest to find Ahilan. Gowrie adopts the blindfold and vows not to remove it until she and all her children are all together again.

Act II takes place in 2009, the devastating final year of the civil war. We are in no doubt about the horrors visited on the population when a corrupt government betrays its people. The government declares camp after camp as safe and then atacks it. The UN Peace Keeping 'blondes' are ineffective and negligent in their abondment of local staff. Chaos and despair rein.

The audience gets periods of relief through humour and joy. The writers equally shine a light on the grace, dignity, resilience and generosity that allows life to go on despite the war. At Sydney's Bennelong restaurant, Siva celebrates his daughter Lakshmi's graduation and is remarkably accepting of her coming out. This last development seems superfluous and played for laughs, as a break from the intensity. Love also triumphs back home withe marriage of Abi, a Hindu, to her childhood sweetheart, a Buddhist, conducted by a Catholic priest. Even if this interfaith ceremony may not provide a realistic model for futer reconciliation, it is a reminder that life and conflicts are complex.

Act III is set in the present and 13 years on from "the beginning of the end". Lakshmi is now a human rights lawyer and back in Sri Lanka on a quest for justice. A government official defends his own role in the tragedy. He wants everyone to move on as reconciliation is not possible when there are "so many truths". "We will tell them all" replies Lakshmi. Resort developers find Ahilan's body, the government forbids a funeral and Abi is willing to risk all to give him one. Gowrie ends up reunited with all her children, but not in the way she dreamt of. She remo

ves her blindfold and the play ends as it started with a haunting dance.

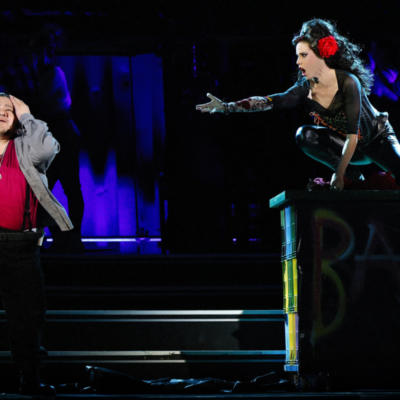

Gowrie is played by Anandavalli, artistic director of the Lingalayam Dance Company and mother of S.Shakthidharan. With such a dignified and strong presence throughout the play, I was surprised to read later that she was a first time actor. The whole cast was brilliant, with particularly strong performances from Prakash Belawadi as Siva and Friar Joseph, Emma Harvie as Lakshmi, Kalieaswari Srinivasan as Abi and Nadee Kammellaweera as Madhu.

The cast is backed by an equally strong creative team. Set design, lighting, sound and music enhance the story. Evocative South Indian played live to the edge of the stage by Indu Balachandran on veena and Arjunan Puveendran on various drums and vocals, ramps up the emotions. A simple bullet pocked set remains a constant while the action is propelled forward by the revolving floor, generating a sense of foreboding, reflecting the passing of time and the incessant movement and instability of refugee life.

After almost three hours of this emotional rollercoaster, the audience is free to go into the night, but reluctant to leave. Groups huddle to dissect, strangers strike up converstations to debrief, wanting to hold onto the moment for reflection. Two weeks later, Gowrie and her family are still occupying my thoughts.

Can there be peace without justice and holding to account those from both sides who committed abuses against civilians? The story is not over for Sri Lanka. A sizeable portion of the Tamil population remains displaced, alienated and over 100,000 people are missing. Justice and truth are still to come. The Jungle And The Sea is not a complete Sri Lankan history and it does not fully address Australia's role in this tragedy. Australia's treatment of Tamil refugees is one amongst the many traumas we've yet to reconcile.

The Jungle And The Sea wraps up a stella 2022 season for The Belvoir Theatre. It's on until 18 December, you should see it.

Photos by Sriram Jeyaraman